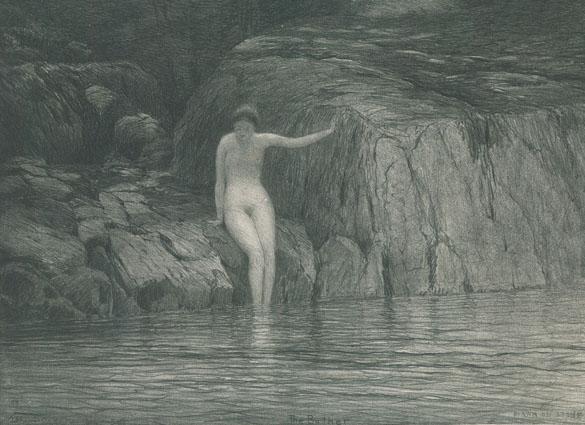

![father-francis-VRT]() Prologue

Prologue

We begin this final installment searching the roots of Woodstock’s mysticism, by seeking at least “a casual relationship” between Woo and Wee-ality by means of further Time Travel. So…back we to go to 1974 when, at the age of 18, I first encountered Robert Thurman at Amherst College. Here, having been forgiven his vows sufficient to marry and father a family, our “first Westerner ordained as Tibetan Buddhist monk” seemed momentarily critical of monasticism, while remaining formidably versed in the traditions of rigorous debate essential to his training as a Gelugpa monk. So it was within this somewhat ambidextrous context, that Professor Thurman first cast a spell upon me (and I suspect, most of our tiny class,) when he flatly announced: “Buddhism at its purest is not a religion, it is a science; in fact, it is the ultimate science.”

Four years later the entire Amherst faculty was uproariously divided when Robert Thurman received full tenure. Rumor soon ran riot of a shootout between this “student’s favorite,” and a universally revered Chairman of the Philosophy Department. Evidently the conflict began when the latter powerhouse, one William Kennick, publicly ridiculed Buddhist philosophy as “mumbojumbo passed between little old brown men wrapped in dirty blankets.” Yet our candidate for tenure astutely avoided direct confrontation, to instead provide his esteemed colleague with a translation of the famous Gelugpa debate proving “All is Void.”

Now to grossly oversimplify a multifaceted and incredibly complex argument, allow this primitive synopsis: In the final analysis, nothing in any universe demonstrates true, independent existence, because all which seems “to be” is either coming into or passing out of a “window of identity” prior to which and beyond which it vanishes. Yet since nothing which firmly and truly “exists” could ever be said to “not exist,” it obviously follows that no phenomena anywhere can actually be said to “ultimately” exist at all. Or, as stated in the initially terrifying teachings of Prince Siddhartha upon his attaining full enlightenment under the Bodhi tree: “All is Void.”

Meanwhile, back at the academic shootout, William Kennick reappeared, only to abruptly rescind all previously disrespectful remarks while admitting: “This text represents a faultless argument — one I wish I’d never read.” And with that, Robert Thurman and “Pure Buddhism” stormed the gates of Western Philosophy.

The point being: the argument Thurman presented Kennick was anything but Woo Woo; however, the four other schools of Tibetan Buddhism — to one degree or another — are indeed dyed in the wool of Woo (due to their strong family resemblance to the original “Bon Po” religion indigenous to Tibet). These four other schools include the powerful Kagyu or “magic” school, whose preeminent monastery on this continent, just so happens to border the Church on the Mount atop Mead’s Mountain in Woodstock, New York.

Lastly, allow word or two concerning Magic (“pure Woo”) vs. “hard” Science. Part I began with creative Woodstock’s financier, Ralph Whitehead, and his 1897 letter to the American Psychical Society, debunking as lunatics a family of “sensitives” who Whitehead ruled had not, authentically, established contact with the dead. Let’s call such fraudulence, “Woo Woo at its Worst.”

So what is “Woo Woo at its Best?” Four years earlier, Nikola Tesla, having lit the entirety of Chicago’s Columbian Exposition with his revolutionary AC currents, here also demonstrated “related technologies” climaxing in his “bathing” himself with hundreds of thousands of volts of electricity. Dressed more as a Magician than scientist, Tesla’s accomplishment defied contemporary explanation, with layman and “electrician” alike, unable to explain Tesla’s survival without resorting to the notion of “Sorcery.” (This “Magician’s trick” employed by the greatest inventor the Earth has ever known, utilized a discovery inducing huge reservoirs of electricity to travel “over” not “through” his own body.) However, the ultimate irony concerning this unique genius, involves the fact that Tesla actually denied and suppressed his powers of telepathy and precognition, even as he used his “acknowledged abilities” to foster the mantle of Magician.

Now in the Twilight Zone of Woo we are about to reenter — exactly as in the life of Nikola Tesla — the lines between fraud, defiance of “contemporary” explanation, and powers which possibly transcend even the understanding of those employing them — indeed, all these distinctions must soon blur and even disappear.

Part III

By 1969, Kalu Rinpoche, the senior meditation master of the Kagyu lineage, had been meditating in forests, crude huts, and deep caves for several decades. It was at one such location, then, that his lineage head — the sixteenth Karmapa — arrived to announce: “Rinpoche, you must end your meditation and take the correct view of Buddha Dharma to the West.” So this Kalu Rinpoche did. Understand, however, that legend surrounding such prolonged meditators among Buddhists (and other tribes of Woo), was and remains so intractably entrenched that myth and reality concerning the accomplishments of such individuals becomes all but indistinguishable.

It was already 1975 and Peter Blum, though he didn’t yet have any official relationship with Buddhism, had been seeking one for a while. Little could he know, however, the notoriety of the tall, catfaced Tibetan fated to fulfill this desire. “Well, somehow or ‘ruther,” recalls Blum, “word got out, ‘there’s this guy up at Loren Standlee’s place in Byrdcliffe who transfers a legit connect to real deal Buddhism.’ So up we went.”

Further understand that Loren Standlee — an undersung legend in his own right — had, by this time, sat at the feet of most of the living saints of India, including a great many Buddhist lamas in exile from Tibet. Loren was actually among the first Westerners to urge such high lamas to come to America in the first place. [All this and more is shared by Loren’s life companion, Ziska Baum, in her posthumous portrait of Standlee found on the web’s “Flower Raj Blog.”]

Consequently, it was within Standlee’s home on Camelot Road, that a more or less “incognito” Kalu Rinpoche, first appeared in Woodstock. And so it was here that Peter Blum and family sought him out, circa ‘75-76. “I went with my wife and our one and a half year old daughter,” Peter remembers, “and we all stood and took refuge…Actually, my daughter took three quarters of refuge. She went through the all the motions but then — you go up and you have a lock of your hair cut off — and she didn’t want to do that. Rinpoche laughed.”

However, it turns out that Peter’s wife, Merrily, was a “somewhat lapsed Roman Catholic [who] still had a statue of the blessed mother…” The result being that Peter and Merrily, “would take the kids up to Father Francis’ (Church on the Mount) for Christmas.” Here, “Midnight mass abounded with a purity which had nothing to do with being Catholic or Buddhist. Father Francis was this beautiful old gnome from another world.”

By now Les Visible [first encountered in Part II] had introduced Peter to Samadhi Fred, (so named for his importance at the ashram of Neem Karoli Baba, Ram Dass’s guru, also from Part II.) Upon Fred’s ever mysterious arrival, these three Dharmateers would go a’bowling for hours on end at the Woodstock Lanes. During one such marathon Fred announced: “The Tibetans are coming. At first the Karmapa was about to buy this land in Carmel for his [North American Seat of a] monastery. The down payment being gifted by some Chinese businessman. It was all set. Then somebody took him for a drive up here. And suddenly he changed his mind: ‘No, this is where our monastery is supposed to be!’” History’s truer report is actually revealed in Ziska Baum’s Flower Raj Blog: “It was during a visit of the great Kalu Rinpoche to [our] home in the early 70s, that Loren drove Kalu Rinpoche up Mead Mountain Road to the top of the mountain where the old Mountain House was for sale. Rinpoche got out of the car, looked around, came back to the house, called the 16th Karmapa and after a few calls was told to buy the land. That was the start of KTD.”

Sure enough, the Tibetans showed up here in force. Naturally, Peter, as the official “guru reviewer,” went up to cover the event for Woodstock Times, with Andrea Barrist Stern accompanying him as photographer. Two resident lamas had been sent by the Karmapa as official delegates: Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche and a very young Bardo Tulku. Blum wrote his article of welcome prior to being swept up in events unforeseeable. “I formally thanked them,” Peter affirms, “but then, after the official press conference, Samadhi Fred said to me: ‘Would you like to be introduced personally to the abbott?’ I said, ‘Sure.’ So Fred took me out to the middle of the field and said, ‘Rinpoche this is Peter…he wants Darshan.’ As you might guess, I wasn’t exactly prepared for this, but I instinctively dropped to one knee and took his hand — as this photo shows. Suddenly everything in the meadow started to throb, and the colors to push like a Photoshop filter transforming ‘what was’ into ‘what must be.’”

Four days later Andrea Stern, who’d been standing at the edge of the field with her camera and a telephoto lens, said to Peter: “Here, I thought you might want this,” [whereupon she handed him a photograph published for a first time here.] Later that same year, in the fall 1978, Peter and family were packing up to move to Holland; Blum having had but this one dramatic interaction with Khenpo.

Then Peter had a dream. “In the dream I walked into the shrine room up at KTD, which was then in the old Mead’s Hotel [since torn down], and Bardo Tulku — who I didn’t know at all except from a distance — was sitting there. So I did a triple prostration and walked out of the room. He smiled. That was the entire dream. [Except that] I stopped smoking. Like [snaps fingers.] The afternoon of the day after this very vivid dream I realized: ‘Oh, I haven’t had a cigarette all day.’ And I hadn’t even thought of having one. So I’m watching…two days, three days — no cigarette. Now Ned Romano was helping many individuals to stop smoking, each them going through hell and back. Me? I told people: I smoke — it’s not a problem. And then? It was gone.”

Peter’s family continued to prepare for Europe. However after two or three weeks off cigarettes Blum called up KTD monastery and said, “I’d like to have an interview with Bardo Tulku.” A long meeting resulted, the gist of which was: no, Bardo Tulku did not send “Peter’s dream” or any miracle accompanying such “down the mountain.” Except, that is, for the fact that all Tibetan prayers (and, for that matter, all Tibetan Prayer Flags) are said to essentially “seed the atmosphere,” with blessings for all sentient beings.

Having acknowledged this, however, what now occurred to the oft-Woo’d mind of your present chronicler, is this…what Kalu Rinpoche, that “Master of Meditation’s deepest Cave” actually recognized atop Mead’s Mountain, aside from auspicious physical conditions, was a rather surprising spiritual energy emanating from “The Chapel of Ease,” long since renamed “The Church on the Mount” by Father Francis. For what the Rinpoche — as well as his superior, the 16th Karmapa — of course understood, was that American Christianity, per se, would be threatened by, and therefore hostile to, the building of a large Buddhist monastery, especially one constructed right next door to a humble Christian chapel.

However, it is now suggested that Kalu Rinpoche immediately intuited Father Francis to be something of an Adept, himself; a theory strongly bolstered by the following fact: Much to the surprise of all, Archbishop Francis immediately proved most warm and welcoming to his Asian brothers. In fact, according to then acolyte, Michael Esposito: “The translators couldn’t keep up with the jokes, winks, and laughter flying between the Karmapa and Father Francis, who’d most graciously invited the Tibetans for tea in the meadow above.”

Indeed this, our good Father’s spiritual charisma, had earlier been clearly recognized by a mind no less scintillating than Bob Dylan’s [see Part I] — even prior to the existential crisis precipitating our poet laureate’s travels to Israel’s Wailing Wall, and eventual conversion to radical Christianity. This same mysterious “something,” we must suspect, provided the purified wonder Peter Blum earlier noted at Christmas’ Midnight Mass (by the yearly end of which, according to Esposito: “The entire chapel would be humming like a spaceship preparing to leave the Earth.”)

A similar phenomenon had likewise been noted by another local treasure, Sweetbryar, who at 15 in ‘64, had run away from home to Woodstock where she beheld (without drugs): “People climbing ladders in air! up at Father Francis’ place.”

This original spiritual vibration, of course, would’ve initially resonated from the frail, soft spoken, often hilarious priest who Mike Esposito traded fame and fortune to follow where ever the old fellow led.

Here a particular and admittedly peculiar notion reasserts itself. Indeed, it’s the very image, coined by Peter Blum, captivating me moments after I encountered this “lively-eyed and mustachioed” individual several months ago and soon inspired our traveling back upon Woodstock’s modern history to glimpse a mystical, almost mythical quality emanating from it.

It’s that the singular character of Father (and Archbishop) William Henry Francis indeed surfaced early on in this exploration, which eventually involved dozens of teachers (along with perhaps a charlatan or two) from foreign lands. Yet all through this exotic parade, this patient patriarch — continually muttering his quips and prayers — invariably and ever cheerfully appears, over and over again.

Somehow eluding cliché, the archetypal figure emerges of a slightly nervous shepherd, anxiously checking upon his flock at various hours all through the long, long night ahead. Finally the picture comes even clearer, still…as the solitary Archbishop, ornately dressed in mostly black with lamp in hand, carefully makes his way through this shadow blotched patch of forest surrounding his tiny chapel. You see him now? Guided by that lantern held just above his waist in that wrenlike wrist? It being the very lantern from which a constant Etheric light twinkles — a light instantly recognizable to that select few, among whom Francis seems to have passed on this, his otherworldly beacon, the very same one which even today continues to shed its protective glow upon this, our valley bathed in shadow below.

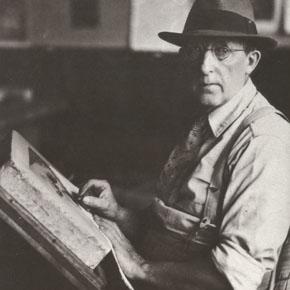

Tad Wise, author of the biographical novel Tesla and coauthor, with Robert Thurman, of Circling The Sacred Mountain, is presently completing The Maverick’s Maverick, a first, full scale biography of Woodstock’s Godfather, Hervey White.